Written by Rachelle Haughn

The Other Side of the Tree Line

As seen in the Fall 2020 issue of Park Pilot

In 1984, Eric Meyers decided that it was time for a change of pace. After Great Planes Model Distributors and Tower Hobbies merged, he was given the opportunity to be his own boss. Eric left Hobbico and helped form a new company called Horizon Hobby (horizonhobby.com). As it turned out, his “high-risk, entrepreneurial adventure” was the right call. He retired from Horizon Hobby in 2012.

Rachelle Haughn: What led you to help found Horizon Hobby?

Eric Meyers: In the 1984 merger … only one president would survive. Our president, Rick Stephens, was out, and when he called and asked if I’d like to be part of a new competing company, I jumped ship. The culture at Hobbico was “restrictive,” so going with him … was stimulating.

In the big picture, Horizon was there to offer hobby shops and suppliers an alternative to Hobbico. While Hobbico held all the cards—the lines, the financing, etc.—we were small and nimble, which we turned into a strength. The market wanted us to succeed, I think.

RH: What types of aircraft were offered when the company was formed?

EM: We were a pure distributor, meaning we sold only product lines like Goldberg, Royal, K&B, Sullivan, Du-Bro—lines everyone had (there were over 50 distributors when we started). In 1985, there weren’t many lines of airplanes available to us. Hobbico had the lead lines like Great Planes and O.S., so Horizon pursued cars in its early years—we were about 90% cars by 1990. Fortunately, cars were very hot, which helped fuel our fast-paced growth.

RH: How did the model aircraft market change while you worked there?

EM: It was easy to see that most consumers, especially beginners, had less time to invest in building. Unlike in the ’40s and ’50s, there were a lot more ways to spend leisure time—think electronic games. So, if we were going to compete as an industry, we had to have time-saving options.

Balsa kits were losing popularity, and the faster that the industry created quality ARFs, the faster they sold. Of course, that went one more step when our developers created BNF (Bind-N-Fly). With BNF, a consumer could get a quality plane and be in the air in minutes. And by and large, the aircraft were straighter, stronger, and more affordable than [what] most people could build on their own.

Eric was lucky that the late Bob Violett took him under his wing and taught him professional-level building, finishing, and setup philosophies.

RH: What was a typical day at the office like for you?

EM: Early on, when Horizon was small, I was involved with growing the company—responsible for both purchasing and marketing, a unique position. That meant I’d buy a product, a line, and already know why it ought to sell. It was a matter of conveying the attributes in [the] New Horizons newsletter.

In the ’80s, a newsletter was progressive, which helped us sell to a national market. With three distribution branches, we grew from nothing to $50 million in sales in just five years. I worked six days a week—didn’t take a lunch for the first two years. But the energy, the teamwork, made it the most fun time of my life.

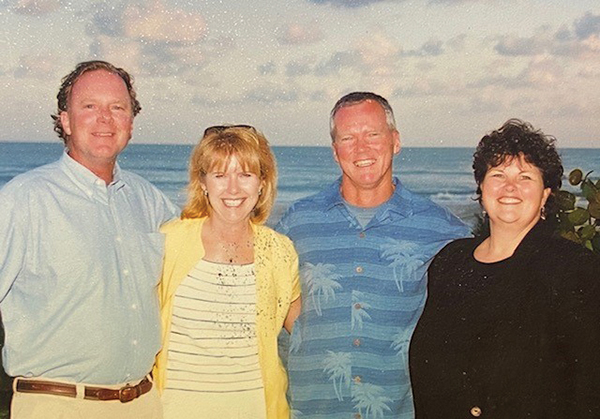

The four who started Horizon Hobby (L-R): Eric, who worked in marketing; Janet Ottmers, sales; Rick Stephens, CEO; and Debra Love, information technology and sales.

This all-carbon-fiber airplane spans 37 inches but flies fast.

RH: Do you remember any ideas that you pitched but never made it into production?

EM: Well, one that I thought had great potential but never happened was having RC air, water, and ground stations and vehicles that shot electronically, with points/scores captured via your cellphone. Take all the gaming concepts, but fly/drive RC. Doesn’t that sound like fun? I pitched it to a number of companies, but it still hasn’t been done.

We also pitched a ground game of “RC Soccerball” to Tamiya and Losi back in the mid-’80s. Looks like Associated did that one, though I’m not sure it’s been a big hit. Getting a big hit takes perfection in every aspect of the marketing plan.

RH: How do you fill your days now that you’re retired?

EM: I’m split between golf and flying. My normal week sees 4 to 5 rounds of golf, and about the same number of times flying. The two are very compatible because they’re both activities that you can take to varying levels. Both are social, outdoors, and challenge the mind. RC takes more indoor prep time, which gives me stuff to do during inclement weather—usually one day a week here in South Carolina. The rest of the time, golf in the morning, fly in the afternoon—not a bad way to spend a day!

RH: What do you enjoy most about the hobby?

EM: I like coaching guys who want to learn. Having made 50 years of mistakes, I have a lot of experience. So, when I find [pilots] who want an accelerated learning curve, I can help them by explaining what I’ve done wrong, how I fixed it, and why one way might work better than another.

For my own flying, I enjoy anything that’s challenging. My brain can’t keep up with some of the toughest maneuvers, so I work on coordination maneuvers.

RH: What do you currently fly?

EM: Mostly 3:1 power-to-weight ratio, 60-size electrics, speed planes, high-performance sport, “big air” scale helicopters, 3D helicopters, turbine jets, EDF jets, and Thermal Duration [Soaring]. All models must be ready for flight in 5 minutes or less. I like to fly a variety of aircraft every day.

RH: How many model aircraft do you own?

EM: Too many. That might sound odd, but you really can have too many. I’ve been giving them away and selling models since I retired, keeping only the best of the best. You know you have too many when you spend more time on maintenance than you do flying them.

Here’s a typical day at the field for Eric, with all major food groups represented. All of this fits in his van. Only the larger jet needs to be assembled.

Eric uses his garages to store his larger airplanes. Throughout the years, he’s figured out how to be fairly space efficient.

Bonus Photos